I may be honing in on part of why I find the American West, not only the landscape but also its people and history, so interesting. And history not necessarily in the wars fought or the great leaders and historic influencers and such, but in the everyday sense. What did people, regular people, do out here? What was their lifeworld? What was their intersubjectivity?

In a way, it’s a manner to defamiliarize myself with my own lifeworld, my own values and needs and hopes and dreams and goals and aspirations and fears… to try on someone else’s to render more explicit to my own consciousness my own silently-held assumptions, biases and predispositions. And if I understand mine better, I can come to know those of others better. I can better empathize with them, knowing that my own convictions and beliefs are sourced in something, sourced in experiences I have had that have influenced my values and thinking, rather than some innate characteristic of mankind that others may or may not have discovered yet.

Indeed, this thought experiment allows me to reject the notion that I have attained some kind of objective, universal, transcendent truth or enlightenment. In some ways I have found my own enlightenment, yes. I have discovered, and continue to hammer out, a personal framework for meaning. But this is not a guarantor. It is something that frames, that helps me make sense of human life, but not something that determines life.

And so, I look to the West, and the ephemera of the 1800s, yes, that era of westward expansion and exploration and such, and I find it fascinating to see what people, what ordinary people, did in those circumstances. What they were forced to do. What they chose to do. How they went about doing it, and why, and what they did once they got there.

And I’m figuring that a lot of the style of the West, artifacts and such that we inescapably associate with the West, are not necessarily by design… but that they were the only resources available from which to craft things. So yes, they were designed, if not in an aesthetic sense, but in that there were strict constraints of materials available to build, and those in turn determined the styles of things, of buildings, of main street in boom towns… indeed, the stark reality of building a town out of nothing, yes, that’s positively fascinating.

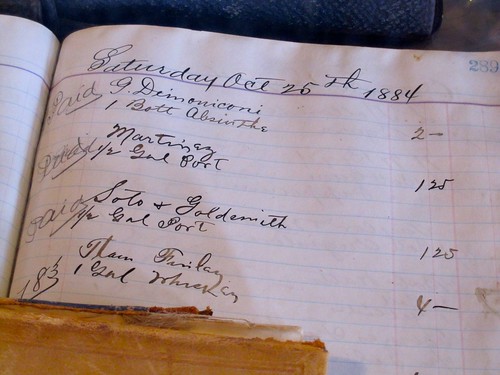

But also, what luxuries did we chose to bring along? From alcohol to prostitutes to sourdough bread to chandeliers in barrooms to player pianos to ornate ceiling tiles to framed art to wainscoting to wallpaper… these things didn’t just come from nowhere. In a lawless land such as the historic American West, it likely ended up there because someone decided they could make a buck by doing it. A piano is heavy and delicate and difficult to transport, but man just as with any bumpin’ night club, I’m sure it could bring the crowds if you were the only saloon that had one.

But also, I’m interested in the West from an art direction standpoint, from the way the western films, with their spurs and pointed-toe cowboy boots and electric guitars and whistles and harmonicas and such, the way Sergio Leone has basically mediated the portrayal of the West, and given us these vast tools of shared meaning with which we can craft and express a certain experience. And, in the case of diagetic sound, that can be pretty authentic, from the sounds of insects to wind to trotting horses, but also the electric guitars and whoops and hollers of The Good, The Bad and The Ugly, how the non-diagetic sound has become a resource for emotional connection and, yes, designed experience.

So there’s West as nature, which I love. There’s West as life, historically, which I find interesting. There’s West as a shared cultural cinematic medium, the experience design of the West, which I find awesome.

And. There’s West as a raw portrayal of what we find quintessentially valuable as Americans. Or even, as humans. As people. I don’t want to draw too many universals independent of American culture, but there’s something telling to the West, the rawness of the hardscrabble life its history afforded, that tells a story of what we truly, truly value, yes as historic Americans, as a culture, but perhaps even as humans, when we have nothing and are presented with the rawest of living.

If we were to carve out an existence where there is nothing (taking on the perspective of a period-era pioneer, for a moment, and blindly ignoring the existing indigenous cultures we oh-so-ravaged, which already had indescribable “meanings” associated with all that we considered wide open “nothing” in the West), what are we going to carry with ourselves on our backs as we make our way westward? What are we going to build once we get there? What are we going to seek out, either from nature, or from others, in the hope that a loose regional society can provide what essentials we cannot provide for ourselves?

What do we value, above all else, such that we will go through such pains to carry it with us, or build it, or seek it out? Shelter, water, food, fame, fortune, power, sex, liquor, the sublime, art, culture, music, the church, tobacco, opium… what motivates us, as a people, even at the fringes of civilization? What remains constant? What do we carry in our hearts, wherever we travel, whatever our society, whatever its wickedness and lawlessness?

In a way, I find the West a fascinating experiment in what we truly find most valuable as a culture, a society, a people, perhaps even a species… a perfected laboratory where, if given an opportunity to start it all over, with limited resources, how we would desire to remake ourselves. The scarcity of resources and obvious constraints and harshness of life in the Old West fascinates me as a designer, perhaps even moreso than the aesthetics of Western life, and I feel I’m beginning to understand that the aesthetics we associate with the West are inexplicably tied to something that was very real, and very raw, for some people’s existence.

The stories of other people’s lives, and how they lived them from day to day, fascinate me as a writer and a storyteller. I continue my attempts to unravel the stories of the West, for I feel as though they hold some kind of truth as to what dwells in the hearts of humankind.